Mole

Member-

Posts

185 -

Joined

-

Days Won

4

Everything posted by Mole

-

In FDR358 (Stef's wager) Stefan argued that it is better to believe in free will when lacking information to its existence. He calls this argument Stef’s wager. If you believe in free will but determinism is true then you were determined to believe in free will so you lost nothing. If you believe in determinism but free will is true then you lost your ability for personal responsibility which is worse. In this post, I will argue against the wager and utilise my argument against the wager to provide a case for, and to defend determinism. I will not cite all my paraphrases of Stefan for obvious reasons, but that is not a problem given that others may correct me if they believe I have misrepresented Stefan. Also, phrases with single quotation marks are quoting Stefan. Free will is defined as that which any person who possesses it could have chosen differently in a circumstance given that the circumstance is unchanged, hence choices being uncaused by any physical effect. Decisions may be caused by something non-material like a soul. Or they may be self-caused, as Stefan has favoured. This definition of free will is the same definition Stefan has used. No sane determinist truly believes that beliefs cannot be changed or that choice does not exist. No sane determinist truly believes people cannot be rational or cannot debate. So naturally, a determinist will probably not find Stef’s wager convincing given that the determinist had probably considered the ability to choose when they adopted their belief in determinism. A determinist will not believe that beliefs cannot be influenced. Therefore, I argue that a better wager would be to show the pragmatic consequences of a determinist morality vs. a free will morality. This is more in line with the original Descartes wager. Descartes did not argue that if you believe in God but God does not exist then you cannot have lost anything because then morality does not exist anyway and so free will doesn't exist and you could not have changed your mind. Rather, he weighed up the consequences of the belief without changing epistemological postulates. He said if you believe in God but there is no God then you have not changed much in your life. If you believe in no God but there is a God then you will go to hell. Nowhere in this argument are one’s epistemological beliefs challenged. The wager is a pragmatic rather than a philosophical argument. Speaking in pragmatic terms, the wager favours neither position particularly strongly. There are many changes that a person makes if they are committed to determinism, for which it would be costly if they didn't make if determinism is true. Firstly, you stop evaluating people based on the decisions they make and start evaluating them on their behaviour. This makes life much simpler because you stop judging your own desires about people. You don't try to convince yourself someone is worth your time because they are trying their best to be a good person. You don't feel guilty for being selfish with regards to your relationships. According to a study, 44% of trait conscientiousness is heritable. This study supports the claim that virtue is predetermined. Secondly, you become compassionate towards others. You understand anger does not appeal to their rationality. Given that you evaluate them on their behaviour, you can infer that they are not worthy of your time if they don't change their behaviour. You may call them stubborn without any need to grant them free will. Thirdly, you have a richer understanding of human nature. How anger could change someone even if free will is true is difficult to imagine. A much simpler approach is to understand our emotions do not necessarily have any moral content. Anger may be a fight or flight mechanism. Shame may be a way of keeping the integrity of a tribe. Hatred depends on subjective values. There is not necessarily an unconscious 'true self' that 'knows everything' and then the extra component of free will. Rather, we can understand how people think by analysing their biology and experiences. According to free will, brain damage may affect a person’s emotions or unconscious motives, but it should not be able to affect a person’s virtue or moral worth, which should be solely determined by free will, and free will not being determined by physical effect. However, a study found that brain damage can casually make changes in the way that people reason which can causally change moral beliefs. Fourthly, you become compassionate towards yourself. A meta-analysis found a large effect size for the negative relationship between self-compassion and psychopathology, r = − 0.54 (95% CI = − 0.57 to − 0.51; Z = − 34.02; p < .0001). We can come to understand that when we say ‘sorry’, we don’t really mean we are worthy of shame, but rather that we understand that we should change how we behave in the future compared to the past. We also stop comparing ourselves to others. Under the dictum that reason equals virtue equals happiness, we may feel compelled to compare our levels of happiness to others, or to compare our virtue to that of others. This is not a good approach. We can accept that we are not all dealt the same hand, and there may as well be things that determine our virtue for which are difficult to control. It is not to say that we ought not to strive for virtue, but that virtue should not necessarily be the determinant of self-esteem. What is more appropriate is to compare oneself in the present to oneself in the past. Stefan has argued that determinism is paradoxical because it presupposes that a person is capable of choice, that is, changing their beliefs, while at the same time asserting that choice is impossible. Determinism is the opposite of free will. So, determinism is defined as not being able to have chosen differently in a circumstance given that the circumstance is unchanged, hence choices being caused by physical effects. According to this definition, whether a person has actually made a choice remains untouched. So, the ability to choose and the fact that a person could not have chosen differently are compatible. Choice itself does not require free will. Choice is the ability to change behaviour in virtue of being rational. Rationality is simply conceptual ‘fidelity to reality’. This does not entail free will. Rationality distinguishes us from animals. Animals cannot think conceptually, and we can. Free will then is not required to distinguish human and animal thought. Stefan has argued that if a determinist attempts to debate because they believe others are 'inputs and outputs', then it explains why other people debate, but it would also mean the determinist is also an input-output machine. And therefore, a determinist has not chosen to debate with others and cannot attempt to debate in the first place which is a performative contradiction. To this argument I rebut. If free will does exist and we are watching two others debate, we can explain their behaviour without appealing to free will by labelling them as inputs and outputs much like philosophical zombies. A determinist simply takes that further to say that this is also a characteristic of the observer. We can still choose to debate even if it was determined. I am yet to have heard a philosophical argument from Stefan against determinism without him appealing to the argument of performative contradiction. If there is no contradiction with the belief of free will, we should look at the evidence and the simplest explanation. Stefan has acknowledged that determinism should be accepted only if it is non-contradictory given that it is simpler. The evidence overwhelmingly supports that determinism is simpler to free will for the following reasons. Firstly, everything else seems to be determined by all effects acting as also as all causes. Stefan has argued that we should not be surprised to find that the human mind possesses free will given that it is only the brain that possesses consciousness. However, I am not sure whether it's correct to assume that only the brain possesses consciousness. Consciousness cannot be objectively observed. If it were not for what we have observed in the physical human body and comparing it to our subjective experience, there would have been no way to know that consciousness resides in the brain. In fact, we still don't really know whether animals are conscious. In that regard, a rock could even be conscious in some manner, a position known as panpsychism. If a computer was capable of conceptual processing, it is likely that the computer would be conscious at a level similar to our own. Consciousness may have to do more with complexity and feedback loops than it has to do with the brain. I had a dream a while ago in which I saw consciousness and life itself arising from feedback loops, weird dream. Secondly, I do not know what it means to feel free. At least from my perspective, I see my thoughts as constant dialectics. I have said sorry enough times to my girlfriend where I really feel like I don't have much control as I thought I had. Do any men concur? Split-brain patients will often have opposing preferences in separate hemispheres. For example, one hemisphere may have atheistic leanings while the other has theistic leanings. Whether the person is actually theistic may have to do with what ever preference dominates consciousness as a unitary experience, but it does go to show the power of causality in the brain. Also, in my experience the biggest changes in my behaviour have arisen from changes in my environment rather than changes in my attitude. Thirdly, morality requires rationality but it does not require free will. Nowhere in the UPB framework is there a requirement for free will. If a person is rational, they will be moral by adopting universal preferences. Whether a person is rational may be predetermined. Fourthly, it is difficult to articulate what free will actually is. If you were asked to pick a random grass leaf from a field, it is difficult to claim you could have chosen differently. Every choice must depend on knowledge. Picking a grass leaf from a field is not an informative decision. You cannot for example say to have free will about whether to steer a ship east or west while in the middle of an unknown ocean at least without some scientific acuity. Likely, you will pick based solely upon gut feelings, or some kind of patterns of thinking or heuristics. Indeed, this is why neuroscientists can predict such behaviour before the person is aware of their decision. But even if a decision were to be more informative, like for example whether to watch this movie or that movie, there is nothing in your environment which informs you about what you ought to do. It is not intrinsically more rational to watch either movie. There is no ought from an is. Now, we can still say that morality exists. We can say it’s rational to be moral, for your behaviour to be universally preferable. However, choosing to watch a movie is not a moral decision. Subjective taste would largely determine which movie to watch, which arises from unconscious processes. If you are rational, unconscious motives will drive your specific behaviours. If you are irrational, unconscious motives will still drive your specific behaviours. Then, free will might not exist in the behavioural decisions per se, but rather in the choice about whether one acts rationally or irrationally regardless of what behaviour that entails. This is certainly what Ayn Rand believed. The point here is that free will how it is typically conceptualised as existing in every choice we make is unnecessary, and creates the problem of supposing some open system where we get inspiration or information from something that is neither in our environment or biology. To conclude, whether or not a person believes in determinism has significant effects on their life regardless of whether determinism is true. Determinism is not incompatible with the ability to choose. Therefore, it does not contradict how we act. Given that determinism is the simplest explanation, determinism is true. Determinism is defined as a lack of the ability have chosen differently. Free willers would argue the corollary to determinism is that choice does not exist. Conventionally then, determinism is also defined as the lack of choice. But I would argue that this belief is the idea of fatalism and not determinism. Given that morality exists and free will is an important concept in moral reasoning, I am in favour of compatibilism which states that free will does not contradict determinism if we define free will conventionally as the ability to choose and determinism as not having been able to have chosen differently. A person who is a compatibilist is still a determinist. I also wish not to do a disservice to free willers by abandoning the term known as free will used to describe the position of believing in the ability to have chosen differently, so I think it is appropriate to call that position free will while separating it from conventional free will.

- 21 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- free will

- determinism

- (and 8 more)

-

If everyone is secretly using their textbook during an exam, what's fairer? I would say to use the textbook. Anyway, it's not even a moral issue there is no ethics in politics. If bribing is the way it works, then that's the system you have to accept.

- 15 replies

-

I have had some time to think and in this post I will attempt to provide a concrete, simple, and intuitive argument for the conscience. I think I my original premise that the conscience is breached from the arbitrary (non-universal) nature of immoral preferences is sound but insufficient for a full argument for the existence of the conscience. I had provided some statements that in my mind I thought were possibilities to complete the argument. "Perhaps it's that irrationality that creates psychological distress in the form of cognitive dissonance. This argument sounds very abstract but perhaps it doesn't need to be known consciously to create that psychological distress. The unconscious mind processes things vastly faster than the conscious mind, so I assume that this is where the conscience would exist." also, "More questions could be raised, such as why does the conscience raise so much guilt compared to non-moral mechanisms? One answer might be that moral judgements are existential in nature. For example, believing in country borders has little to do with your wellbeing. But if you are a murderer, the kind of distress you would feel would be epistemologically equivalent to as if you were being murdered yourself because the unconscious mind wouldn't be able to objectively distinguish you from the other person and so would have to sort of assume you are the other person. " In retrospect, I think these explanations are unnecessary, to say the least. I am not sure whether @Philociraptor agreed with my original premise that the conscience is breached from the arbitrary nature of immoral preferences, but I do now think that Philociraptor's premise that "conscience is just the ability to determine right from wrong" is sound given that one can act against their conscience. So, inevitably I combine these two premises and say that the ability to determine right from wrong will be breached when preferences are arbitrary in nature. My fulll argument for the conscience goes as follows: Knowledge is derived from reality. We are born as blank slates. Only existence can be known because only existence exists. Reality is consistent. Should be easy enough to understand. Therefore, knowledge is universal. If the earth is round for me, it is also round for you. Preferences are knowledge claims. To have a preference for theft is to claim that 'I ought to steal'. Therefore, preferences must be universal in order to be valid knowledge. If I ought to steal, then it must be as much true for you as it is true for me. A contradiction arises because if I prefer to steal, you must necessarily prefer that I don't steal which means that the preference is not universal and not valid knowledge. We can see that a preference for theft is irrational, but how does this affect the conscience? Consciousness requires knowledge. I cannot be conscious of anything if I have no knowledge of anything. Therefore, arbitrary preferences negate consciousness. If a person acts upon irrational beliefs, their knowledge about reality becomes distorted. They become moral subjectivists. And inevitably they must lose their consciousness relative to the degree that they have less understanding of reality. Consciousness cannot exist without the conscience, without that ability to evaluate what is rational and irrational. Some people will not have a conscience, but those who wish to survive and value themselves will have one. I am not sure whether Philociraptor was thinking in the same terms, but it is somewhat true what Philociraptor said: "As hard as it may seem to accept, they [evil people] are not at all like us. They just aren't actually humans. More like zombies... some kind of parasite or some kind of biological robot. Something like that." The argument for the conscience may be used to reason such a circumstance: Let's say my friend has an annoying habit of overspeaking. If I permit it, I am suggesting that his habit is of value to the conversation when I believe that it is not. This not universally preferable because my permittance neccesitates that I hold a preference against his habit while he holds a preference for it. This contradiction must mean the preference does not reflect reality and so is not within my rational self-interest. So, even if it creates some discomfort, if I wish to be rational and subsist and have enough self-esteem, I must be honest and let him know that I find his habit annoying. In short-hand, people will not lie often because lying is simply wrong. It is intuitive. Truly, the decision here is whether to be rational or irrational. In fact, I would say all decisions are like this. I would say that preferences and behaviour among universally preferable alternatives such as which piece of art someone prefers and chooses is determined by subjective taste, which in turn is determined by subjective biology and subjective experience, I.e., universally preferable behaviour is conditioned or instinctual. This is not to say, however, that those subjective experiences had not included moral content. For example, one can have a taste for objectively ugly art and that taste could be determined by the immoral choices the person had made in the past, and those choices are not deterministic, however, the taste itself is still determined. Moral choices may never have had much of a factor. Perhaps the person was born with disposition towards that art for some reason. Either possibility does not invalidate the claim that preferences and behaviour among universally preferable alternatives are determined. Of course, then there must be some mechanism for such conditioning to be processed. Thankfully, unconscious drives fits right into the hypothesis. There is little doubt that these do exist. It is unconscious drives that in fact create the dillema of choosing between universal preferable behaviour (morality) and universally proscribed behaviour (immorality) in the first place. There must be something that entices a person to act irrationaly. If a person has a choice to either be rational and subsist, or be irrational and perish, it may seem obvious that the person would want to be rational if there are no other consequences. But this is not what happens. People do bad things all the time. People conform. People lie. People murder. This behaviour can be explained by unconscious drives. One can be rational, but the consequence is that they will feel discomfort for it because their unconscious drives are affecting their emotion. Preferences and behaviour among universally proscribed alternatives are determined when one is irrational. A murderer must have been predisposed towards it, via conditioning or instinct. That predisposition was determined. It does not mean he does not have a choice. He has a choice whether to murder, but he cannot choose whether those predispositions exist; whether he has an urge to murder. The real choice here is between being rational or irrational. The content of those alternatives are determined. In other words, preferences and behaviour among universally proscribed alternatives iwhen one is irrational are conditioned or instinctual. So, preferences and behaviour among universally preferable alternatives is determined when one is rational. Preferences and behaviour among universally proscribed behaviour is determined when one is irrational. We may call the sum predispositions or unconscious drives of these preferences and behaviours the true self and false self, respectively. The conscience resides here. However, preferences and behaviour between universallly preferable and universally proscribed alternatives are not determined. This is the only area wherein free will and consciousness exist. One is either rational and acts as what ever was already determined by the true self or irrational and acts as what ever was already determined by the false self. Philosophy can only go so far and the mechanisms of these unconscious drives is the job of psychology.

-

An evil person is not good and a good person is not evil. So a person who knows good cannot choose evil as well? I get these are opposites, but what does it have to do with the knowledge of good and evil?

-

So what did you mean it's not a choice? That it is indeed objective? You're giving me your position on the objectivity of morality. I understand your view on the objectivity of morality already, and I appreciate you are trying to explain it to me but that's not what I'm stuck on. What I'm stuck on is that I really don't know what you meant by 'it's not a choice'. That's why I'm trying to ask you precise questions so I can eliminate potential positions you might hold in my mind, and also so it can be easy for you to answer them in a short way and without having to try to figure out what I'm thinking or what I'm not getting.

-

What do you mean it's not a choice? You mean that morality is objective? Or you mean people are determined to be moral if they know what is moral?

-

There seems to be two concepts you are presenting here. The first is that mother nature takes care of immoral people, but I don't see why we should assume that. I think immorality will have psychological effects on people, but not necessarily concerning their liberty or safety. The second concept is that people who know what is moral are always moral. If people know what liberty is, they will respect it. This second concept interests me because it could answer my topic question. The proof of the conscience would be that morality is objective (as you have said) and conscience is knowledge of morality, and that people will act morally because of this knowledge so that the knowledge of morality and the inclination to act morally are really the same thing. I would like to know why you think it is the case though that knowledge of morality necessarily means acting morally?

-

However, not all murderers are killed. Are you suggesting that the only reason why people should be moral is for the sake of their own liberty and safety?

-

If I'm an immoral person, how will my actions affect me?

-

What is the causal relationship between immorality and reward or punishment?

-

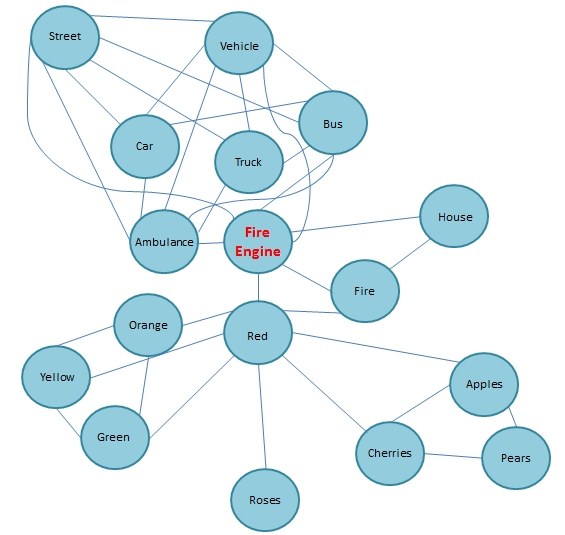

If I understand the decision tree correctly, only the collection of descriptors is something real. Like a spherical green thing is real, but the meaning we give to it, either apple or tennis ball is not real? Maybe it would work for chair, however, something like an apple has very specific descriptors. Perhaps we would say an apple is real but a chair isn't? You might be interested in semantic network theories. It's a bit different to the decision tree though, because everything kind of has meaning as its own thing. No 'root'. When asked the question 'is a fire engine red?', the concepts fire engine and red are activated in the brains neural network. Because they are in close proximity, the answer comes fast. But if you were asked 'Is a fire engine a vehicle?' it might take you a split second faster to answer.

-

Is it a reply to my karmic force comment? Can't seem to find it, unfortunately.

-

I think what is likely is that we had ideas in our minds which we acted upon for natural adaptation purposes. But soon enough these ideas became maladaptive for natural adaptation purposes. I find it hard to argue against this given that virtually everything we do has been so vigorously conditioned that it has been virtually cut off from the preceding unconditioned stimuli. The thoughts still existed, however, so rather than our behaviour and corresponding thoughts being adaptations, the thoughts exist as entities in their own right. Now those thoughts give rise to cultural evolution. The key difference it has from natural selection is that the thoughts that survive are those that are rational. Let me give an example of what I'm trying to say here. Early in our species development, we may have formed the idea that "subjugation is moral". This would be adaptive for both the authorities and for the subordinates. After some technological progress perhaps self-defence becomes more feasible and there is no longer an adaptive need for this moral judgement. However, the moral judgement still exists. Psychologically, our mind still believed that this moral judgement is good for our survival, or more accurately, it's just preferred or good (I don't think the brain knows what is good for your survival, rather it just knows what's 'good'; it simply prefers or doesn't prefer). So naturally, the idea will try to survive. It will compete against other ideas within the brain. What emerges is an identity. A person. These ideas will only survive if they conform logical consistency and empirical evidence. If they don't, they run into each other but only one can then survive. This allows for rationality, and universal morality where morality is no longer an adaptation towards genetic survival but rather towards the survival of the idea itself, and hence the survival of the mind or ego as the mind is nothing but a bunch of ideas. If we think of ideas themselves as 'selfish genes', I think it can revolutionalise how we think of ethics.

-

How does this karmic force work? What proof is there for it?

-

How does this karmic force work? What proof is there for it?

-

Of course, an evolutionary perspective raises the concern of what is morally right when evolution tells us to do destructive things like be a parasite or be patriotic or go to war. Or more personally not to be critical of those around you.

-

Politicians and welfare recipients aren't destroyed. In fact, their immoral behaviour keeps them going.

-

The government hurts others. The government hasn't been destroyed. Politicians don't die. Welfare recipients aren't destroyed.

-

What are you implying with that definition?

-

Hurting people is wrong and it affects you. It affects you because you feel sympathy. You feel sympathy because you have a conscience. Your conscience says that hurting people is wrong. Why is hurting people wrong?

-

You said that the conscience is the ability to determine what is right and wrong. Then what is sympathy? Isn't sympathy the conscience? Or is sympathy also the ability to determine what is right and wrong?

-

You said that the conscience is the ability to determine what is right and wrong. Then what is sympathy? Isn't sympathy the conscience? Or is sympathy also the ability to determine what is right and wrong?

-

I see. So how do we determine how immoral acts would affect you?

-

Some things affect you and some things don't.

-

So hurting people is wrong. And what is wrong is saying 'there is no right and wrong' because that shows a preference to believe that 'there is no right and wrong' is right. What do they share in common? I know from reading UPB that what they share in common is that neither is universally preferable. To say 'hurting people is right' is to prefer to not to be hurt.